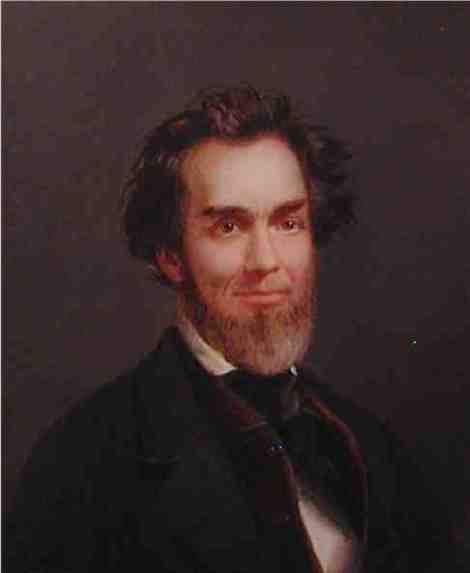

On the eve of the 25th Anniversary of the Battle of North Point, a prominent physician of medicine and purveyor of his famous “Houck’s Remedies” gave to the State of Maryland an acre of land on the battlefield for the princely sum of One Dollar. His gift today is known as Battle Acre along the North Point Road in Baltimore County.

He was born in Frederick County, the son of a prominent merchant, and came to be a graduate of the Maryland University School of Medicine. In December 1839 he purchased the land called “Swan Harbour” and soon thereafter built “one of the most splendid hotels in the vicinity,” that became known as “Houck’s Pavilion” that for years thereafter served as a prominent annual commemorative gathering site for the Old Defenders’ of Baltimore.

The following is an extract of the deed of land to the State of Maryland.

“Know all men by these presents, that I Jacob Houck of the city and county of Baltimore in the State of Maryland am held and firmly bound unto the State of Maryland in the full and just sum of one Dollar lawful money to be paid to the said state, or to its attorney to the payment whereof. I bind myself, my heirs Executors and Administrators firmly by these presents, sealed with my seal, and dated this eleventh day of September in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and thirty nine.

Whereas the said Jacob Houck in consideration of the sum of one dollar to him paid at or before the sealing and delivery hereof, the receipt whereof is hereby acknowledged and also delivered good causes and valuable considerations herein thereunto moving, hath contracted to give grant and convey or to cause and procure to be granted and conveyed unto the said state this or part of a tract, piece or parcel of herein after described the same constituting a part of the North Point Battle Ground “for the purpose of erecting a Monument thereon.” Now the Condition of the foregoing obligation is such, that the said Jacob Houck, or his heirs do and shall within six months next ensuing the date hereof, grant and convey, or cause and procure to be granted and conveyed to the State of Maryland aforesaid, to be held by the said State for ever, for the use and purpose aforesaid. All that Lot or parcel of Land situated and lying in Baltimore County aforesaid being part of a tract called “Swan Harbour” which is contained within the meter and bounds, courses and distances following, that is to say; Beginning for the same part at a stone standing in the ground on the southwestern most side of the road leaving from the City of Baltimore to North Point…” [the remainder of document shows survey points of distances.]

For 75 years no monument was erected, despite the elaborated ceremonies held on September 12, 1839. A granite monument was finally dedicated in 1914 on the centennial of the battle.

Jacob Wever Houck was the father of Mrs. Ella Virginia Houck (Mrs. Reuben Ross Holloway/1862-1940) who often was described as the “number one patriot in Baltimore” who consistently advocated for the making The Star-Spangled Banner” the official national anthem and other patriotic causes. Dr. Jacob Houck, Sr. died in 1850 and is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery in West Baltimore.

Source: Baltimore County Court (Land Records) TK 292, pp. 246-247 Jacob Houck, “Swan Harbor,” 11 September 1839 [MSA CE 66-342]. His son, not to be confused with his father, was Dr. Jacob Wever Houck, Jr. (1822-1888); The Sun, May 23, 1888.

You must be logged in to post a comment.